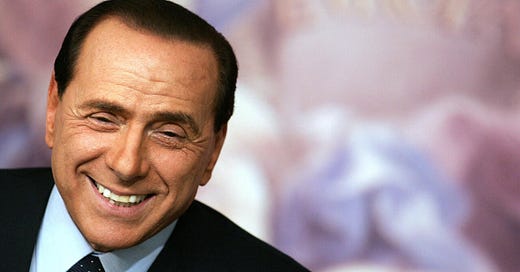

Italy’s Silvio Berlusconi, a billionaire media magnate who died two years ago, won three elections and dominated the country’s political landscape for at least a decade. His governing style resembled that of the Roman emperors. He gave the people panem et circenses, or bread and entertainment, which in Roman times was chariot races at the Circus Maximus.

That is to say that his aim was to generate public admiration and dominate the national narrative by entertaining and distracting the public instead of by providing them enlightened policies or hardscrabble service.

I know because it was my job to report on Berlusconi for more than 20 years. I followed him around the world to international summits, to Sicily for party rallies, and once at an EU summit in Brussels he even put me on his list of “imbecile” journalists after I asked a particularly prickly question. Many times Berlusconi has been described as the original Donald Trump, and there are many similarities.

Berlusconi was the absolute king of making performative political pronouncements that qualified as “news”, but which in reality were hollow or of little importance in the grand scheme of things. Sometimes he would just do silly stunts like hold up two fingers like horns during a group photo behind the head of the Spanish prime minister. Instant front-page picture.

His most common ploy was to attack the magistrates investigating and prosecuting him, much as Trump has done. Berlusconi always found a way of saying something, or doing something, controversial. One time he flustered German Chancellor Angela Merkel, making her wait 15 minutes as he nonchalantly spoke on his mobile phone as she was waiting to greet him at a NATO summit photo op. The whole thing was broadcast live on Italian and other European TV channels.

For journalists he was, as one of my former editors put it, the gift that keeps on giving. Berlusconi’s goal was to be on the front page, above the fold, every day, and to leave his rivals starving for media oxygen and unable to dictate the political narrative. For Berlusconi, all publicity was good publicity. He was shameless.

Trump is the same, except he’s the so-called leader of the free world. He is sitting atop the world’s most successful economy and its most lethal military.

One recent example of such an performative announcement is Trump’s inauguration-day declaration that the Gulf of Mexico be renamed (at least for Americans using Google Maps) the Gulf of America. With the strike of a pen, Trump sent a message to his Mexican-immigration-obsessed supporters and gave them something to cheer about, while the rest of us had a hearty chuckle.

Another example that most of us are not laughing about is his tariff threat against Canada and Mexico, two of America’s biggest trading partners and historic allies. Berlusconi never wielded such a potentially destructive weapon as the American economy. It is unclear what Trump’s end-game could be for a trade war, which would wreak havoc on consumers in the United States as well. It’s likely he doesn’t have one. Instead it serves as a distraction. The threat has been set aside for a few weeks, but it will be back.

Why? Because there is nothing more entertaining to the media and the general public than a good fight!

As a journalist I have been guilty of this more times than I can count, whether it was Berlusconi battling left-leaning magistrates or Canadian PM Justin Trudeau bickering with Alberta Premier Danielle Smith over energy policy. More recently, Trudeau fought with his own Deputy PM Chrystia Freeland, and well, he lost. Some political fights do have clear losers and consequences, but most do not.

The best headlines and first paragraphs to news stories are the ones packed with tension, with at least two sides clashing and the outcome uncertain. Readers gobble those stories up, and as reporters we feed the beast.

My conclusion after many years of being bamboozled by Berlusconi was that the best way not to be bamboozled was to ignore him altogether. That was difficult, especially since his denouement involved stories about Muamar Qaddafi-inspired “bunga bunga” orgies and a harem of extremely young prostitutes. It turns out that some publicity is bad.

Usually nothing came of Berlusconi’s mock disputes, stunts and gaffes. A day later, they lined Italy’s birdcages. They were a put-on to keep Berlusconi’s core supporters interested. Trump’s fights have the same function. He wants to entertain his supporters, keep them engaged. To do that he dons boxing gloves and throws a few punches. Even if he fails to land a solid blow, he can bow out in the first round and claim victory.

What is scary is that the President of the United States is the most powerful man in the world. Berlusconi was not. Trump’s fights, even if they’re fake, make millions of people nervous because they could have devastating consequences. But Trump’s voters are clapping and cheering, and no matter how much we want to, we can’t take our eyes off of him.

.